🌍 Čeština ∙ Deutsch ∙ Ελληνικά ∙ English ∙ Español ∙ Français ∙ Italiano ∙ 日本語 ∙ 한국어 ∙ Português ∙ Русский ∙ Slovenščina ∙ Українська ∙ 简体中文 ∙ 繁體中文

The Art of Command Line

- Meta

- Basics

- Everyday use

- Processing files and data

- System debugging

- One-liners

- Obscure but useful

- OS X only

- Windows only

- More resources

- Disclaimer

Fluency on the command line is a skill often neglected or considered arcane, but it improves your flexibility and productivity as an engineer in both obvious and subtle ways. This is a selection of notes and tips on using the command-line that we've found useful when working on Linux. Some tips are elementary, and some are fairly specific, sophisticated, or obscure. This page is not long, but if you can use and recall all the items here, you know a lot.

This work is the result of many authors and translators. Some of this originally appeared on Quora, but it has since moved to GitHub, where people more talented than the original author have made numerous improvements. Please submit a question if you have a question related to the command line. Please contribute if you see an error or something that could be better!

Meta

Scope:

- This guide is both for beginners and the experienced. The goals are breadth (everything important), specificity (give concrete examples of the most common case), and brevity (avoid things that aren't essential or digressions you can easily look up elsewhere). Every tip is essential in some situation or significantly saves time over alternatives.

- This is written for Linux, with the exception of the "OS X only" and "Windows only" sections. Many of the other items apply or can be installed on other Unices or OS X (or even Cygwin).

- The focus is on interactive Bash, though many tips apply to other shells and to general Bash scripting.

- It includes both "standard" Unix commands as well as ones that require special package installs -- so long as they are important enough to merit inclusion.

Notes:

- To keep this to one page, content is implicitly included by reference. You're smart enough to look up more detail elsewhere once you know the idea or command to Google. Use

apt-get,yum,dnf,pacman,piporbrew(as appropriate) to install new programs. - Use Explainshell to get a helpful breakdown of what commands, options, pipes etc. do.

Basics

-

Learn basic Bash. Actually, type

man bashand at least skim the whole thing; it's pretty easy to follow and not that long. Alternate shells can be nice, but Bash is powerful and always available (learning only zsh, fish, etc., while tempting on your own laptop, restricts you in many situations, such as using existing servers). -

Learn at least one text-based editor well. Ideally Vim (

vi), as there's really no competition for random editing in a terminal (even if you use Emacs, a big IDE, or a modern hipster editor most of the time). -

Know how to read documentation with

man(for the inquisitive,man manlists the section numbers, e.g. 1 is "regular" commands, 5 is files/conventions, and 8 are for administration). Find man pages withapropos. Know that some commands are not executables, but Bash builtins, and that you can get help on them withhelpandhelp -d. You can find out whether a command is an executable, shell builtin or an alias by usingtype command. -

Learn about redirection of output and input using

>and<and pipes using|. Know>overwrites the output file and>>appends. Learn about stdout and stderr. -

Learn about file glob expansion with

*(and perhaps?and[...]) and quoting and the difference between double"and single'quotes. (See more on variable expansion below.) -

Be familiar with Bash job management:

&, ctrl-z, ctrl-c,jobs,fg,bg,kill, etc. -

Know

ssh, and the basics of passwordless authentication, viassh-agent,ssh-add, etc. -

Basic file management:

lsandls -l(in particular, learn what every column inls -lmeans),less,head,tailandtail -f(or even better,less +F),lnandln -s(learn the differences and advantages of hard versus soft links),chown,chmod,du(for a quick summary of disk usage:du -hs *). For filesystem management,df,mount,fdisk,mkfs,lsblk. Learn what an inode is (ls -iordf -i). -

Basic network management:

iporifconfig,dig. -

Learn and use a version control management system, such as

git. -

Know regular expressions well, and the various flags to

grep/egrep. The-i,-o,-v,-A,-B, and-Coptions are worth knowing. -

Learn to use

apt-get,yum,dnforpacman(depending on distro) to find and install packages. And make sure you havepipto install Python-based command-line tools (a few below are easiest to install viapip).

Everyday use

-

In Bash, use Tab to complete arguments or list all available commands and ctrl-r to search through command history (after pressing, type to search, press ctrl-r repeatedly to cycle through more matches, press Enter to execute the found command, or hit the right arrow to put the result in the current line to allow editing).

-

In Bash, use ctrl-w to delete the last word, and ctrl-u to delete all the way back to the start of the line. Use alt-b and alt-f to move by word, ctrl-a to move cursor to beginning of line, ctrl-e to move cursor to end of line, ctrl-k to kill to the end of the line, ctrl-l to clear the screen. See

man readlinefor all the default keybindings in Bash. There are a lot. For example alt-. cycles through previous arguments, and alt-* expands a glob. -

Alternatively, if you love vi-style key-bindings, use

set -o vi(andset -o emacsto put it back). -

For editing long commands, after setting your editor (for example

export EDITOR=vim), ctrl-x ctrl-e will open the current command in an editor for multi-line editing. Or in vi style, escape-v. -

To see recent commands, use

history. Follow with!n(wherenis the command number) to execute again. There are also many abbreviations you can use, the most useful probably being!$for last argument and!!for last command (see "HISTORY EXPANSION" in the man page). However, these are often easily replaced with ctrl-r and alt-.. -

Go to your home directory with

cd. Access files relative to your home directory with the~prefix (e.g.~/.bashrc). Inshscripts refer to the home directory as$HOME. -

To go back to the previous working directory:

cd -. -

If you are halfway through typing a command but change your mind, hit alt-# to add a

#at the beginning and enter it as a comment (or use ctrl-a, #, enter). You can then return to it later via command history. -

Use

xargs(orparallel). It's very powerful. Note you can control how many items execute per line (-L) as well as parallelism (-P). If you're not sure if it'll do the right thing, usexargs echofirst. Also,-I{}is handy. Examples:

find . -name '*.py' | xargs grep some_function

cat hosts | xargs -I{} ssh root@{} hostname

-

pstree -pis a helpful display of the process tree. -

Use

pgrepandpkillto find or signal processes by name (-fis helpful). -

Know the various signals you can send processes. For example, to suspend a process, use

kill -STOP [pid]. For the full list, seeman 7 signal -

Use

nohupordisownif you want a background process to keep running forever. -

Check what processes are listening via

netstat -lntporss -plat(for TCP; add-ufor UDP). -

See also

lsoffor open sockets and files. -

See

uptimeorwto know how long the system has been running. -

Use

aliasto create shortcuts for commonly used commands. For example,alias ll='ls -latr'creates a new aliasll. -

Save aliases, shell settings, and functions you commonly use in

~/.bashrc, and arrange for login shells to source it. This will make your setup available in all your shell sessions. -

Put the settings of environment variables as well as commands that should be executed when you login in

~/.bash_profile. Separate configuration will be needed for shells you launch from graphical environment logins andcronjobs. -

Synchronize your configuration files (e.g.

.bashrcand.bash_profile) among various computers with Git. -

Understand that care is needed when variables and filenames include whitespace. Surround your Bash variables with quotes, e.g.

"$FOO". Prefer the-0or-print0options to enable null characters to delimit filenames, e.g.locate -0 pattern | xargs -0 ls -alorfind / -print0 -type d | xargs -0 ls -al. To iterate on filenames containing whitespace in a for loop, set your IFS to be a newline only usingIFS=$'\n'. -

In Bash scripts, use

set -x(or the variantset -v, which logs raw input, including unexpanded variables and comments) for debugging output. Use strict modes unless you have a good reason not to: Useset -eto abort on errors (nonzero exit code). Useset -uto detect unset variable usages. Considerset -o pipefailtoo, to on errors within pipes, too (though read up on it more if you do, as this topic is a bit subtle). For more involved scripts, also usetrapon EXIT or ERR. A useful habit is to start a script like this, which will make it detect and abort on common errors and print a message:

set -euo pipefail

trap "echo 'error: Script failed: see failed command above'" ERR

- In Bash scripts, subshells (written with parentheses) are convenient ways to group commands. A common example is to temporarily move to a different working directory, e.g.

# do something in current dir

(cd /some/other/dir && other-command)

# continue in original dir

-

In Bash, note there are lots of kinds of variable expansion. Checking a variable exists:

${name:?error message}. For example, if a Bash script requires a single argument, just writeinput_file=${1:?usage: $0 input_file}. Using a default value if a variable is empty:${name:-default}. If you want to have an additional (optional) parameter added to the previous example, you can use something likeoutput_file=${2:-logfile}. If $2 is omitted and thus empty,output_filewill be set tologfile. Arithmetic expansion:i=$(( (i + 1) % 5 )). Sequences:{1..10}. Trimming of strings:${var%suffix}and${var#prefix}. For example ifvar=foo.pdf, thenecho ${var%.pdf}.txtprintsfoo.txt. -

Brace expansion using

{...}can reduce having to re-type similar text and automate combinations of items. This is helpful in examples likemv foo.{txt,pdf} some-dir(which moves both files),cp somefile{,.bak}(which expands tocp somefile somefile.bak) ormkdir -p test-{a,b,c}/subtest-{1,2,3}(which expands all possible combinations and creates a directory tree). -

The output of a command can be treated like a file via

<(some command). For example, compare local/etc/hostswith a remote one:

diff /etc/hosts <(ssh somehost cat /etc/hosts)

- When writing scripts you may want to put all of your code in curly braces. If the closing brace is missing, your script will be prevented from executing due to a syntax error. This makes sense when your script is going to be downloaded from the web, since it prevents partially downloaded scripts from executing:

{

# Your code here

}

-

Know about "here documents" in Bash, as in

cat <<EOF .... -

In Bash, redirect both standard output and standard error via:

some-command >logfile 2>&1orsome-command &>logfile. Often, to ensure a command does not leave an open file handle to standard input, tying it to the terminal you are in, it is also good practice to add</dev/null. -

Use

man asciifor a good ASCII table, with hex and decimal values. For general encoding info,man unicode,man utf-8, andman latin1are helpful. -

Use

screenortmuxto multiplex the screen, especially useful on remote ssh sessions and to detach and re-attach to a session.byobucan enhance screen or tmux providing more information and easier management. A more minimal alternative for session persistence only isdtach. -

In ssh, knowing how to port tunnel with

-Lor-D(and occasionally-R) is useful, e.g. to access web sites from a remote server. -

It can be useful to make a few optimizations to your ssh configuration; for example, this

~/.ssh/configcontains settings to avoid dropped connections in certain network environments, uses compression (which is helpful with scp over low-bandwidth connections), and multiplex channels to the same server with a local control file:

TCPKeepAlive=yes

ServerAliveInterval=15

ServerAliveCountMax=6

Compression=yes

ControlMaster auto

ControlPath /tmp/%r@%h:%p

ControlPersist yes

-

A few other options relevant to ssh are security sensitive and should be enabled with care, e.g. per subnet or host or in trusted networks:

StrictHostKeyChecking=no,ForwardAgent=yes -

Consider

moshan alternative to ssh that uses UDP, avoiding dropped connections and adding convenience on the road (requires server-side setup). -

To get the permissions on a file in octal form, which is useful for system configuration but not available in

lsand easy to bungle, use something like

stat -c '%A %a %n' /etc/timezone

-

For interactive selection of values from the output of another command, use

percolorfzf. -

For interaction with files based on the output of another command (like

git), usefpp(PathPicker). -

For a simple web server for all files in the current directory (and subdirs), available to anyone on your network, use:

python -m SimpleHTTPServer 7777(for port 7777 and Python 2) andpython -m http.server 7777(for port 7777 and Python 3). -

For running a command as another user, use

sudo. Defaults to running as root; use-uto specify another user. Use-ito login as that user (you will be asked for your password). -

For switching the shell to another user, use

su usernameorsu - username. The latter with "-" gets an environment as if another user just logged in. Omitting the username defaults to root. You will be asked for the password of the user you are switching to. -

Know about the 128K limit on command lines. This "Argument list too long" error is common when wildcard matching large numbers of files. (When this happens alternatives like

findandxargsmay help.) -

For a basic calculator (and of course access to Python in general), use the

pythoninterpreter. For example,

>>> 2+3

5

Processing files and data

-

To locate a file by name in the current directory,

find . -iname '*something*'(or similar). To find a file anywhere by name, uselocate something(but bear in mindupdatedbmay not have indexed recently created files). -

For general searching through source or data files (more advanced than

grep -r), useag. -

To convert HTML to text:

lynx -dump -stdin -

For Markdown, HTML, and all kinds of document conversion, try

pandoc. -

If you must handle XML,

xmlstarletis old but good. -

For JSON, use

jq. -

For YAML, use

shyaml. -

For Excel or CSV files, csvkit provides

in2csv,csvcut,csvjoin,csvgrep, etc. -

For Amazon S3,

s3cmdis convenient ands4cmdis faster. Amazon'sawsand the improvedsawsare essential for other AWS-related tasks. -

Know about

sortanduniq, including uniq's-uand-doptions -- see one-liners below. See alsocomm. -

Know about

cut,paste, andjointo manipulate text files. Many people usecutbut forget aboutjoin. -

Know about

wcto count newlines (-l), characters (-m), words (-w) and bytes (-c). -

Know about

teeto copy from stdin to a file and also to stdout, as inls -al | tee file.txt. -

For more complex calculations, including grouping, reversing fields, and statistical calculations, consider

datamash. -

Know that locale affects a lot of command line tools in subtle ways, including sorting order (collation) and performance. Most Linux installations will set

LANGor other locale variables to a local setting like US English. But be aware sorting will change if you change locale. And know i18n routines can make sort or other commands run many times slower. In some situations (such as the set operations or uniqueness operations below) you can safely ignore slow i18n routines entirely and use traditional byte-based sort order, usingexport LC_ALL=C. -

You can set a specific command's environment by prefixing its invocation with the environment variable settings, as in

TZ=Pacific/Fiji date. -

Know basic

awkandsedfor simple data munging. For example, summing all numbers in the third column of a text file:awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }'. This is probably 3X faster and 3X shorter than equivalent Python. -

To replace all occurrences of a string in place, in one or more files:

perl -pi.bak -e 's/old-string/new-string/g' my-files-*.txt

- To rename multiple files and/or search and replace within files, try

repren. (In some cases therenamecommand also allows multiple renames, but be careful as its functionality is not the same on all Linux distributions.)

# Full rename of filenames, directories, and contents foo -> bar:

repren --full --preserve-case --from foo --to bar .

# Recover backup files whatever.bak -> whatever:

repren --renames --from '(.*)\.bak' --to '\1' *.bak

# Same as above, using rename, if available:

rename 's/\.bak$//' *.bak

- As the man page says,

rsyncreally is a fast and extraordinarily versatile file copying tool. It's known for synchronizing between machines but is equally useful locally. When security restrictions allow, usingrsyncinstead ofscpallows recovery of a transfer without restarting from scratch. It also is among the fastest ways to delete large numbers of files:

mkdir empty && rsync -r --delete empty/ some-dir && rmdir some-dir

-

Use

shufto shuffle or select random lines from a file. -

Know

sort's options. For numbers, use-n, or-hfor handling human-readable numbers (e.g. fromdu -h). Know how keys work (-tand-k). In particular, watch out that you need to write-k1,1to sort by only the first field;-k1means sort according to the whole line. Stable sort (sort -s) can be useful. For example, to sort first by field 2, then secondarily by field 1, you can usesort -k1,1 | sort -s -k2,2. -

If you ever need to write a tab literal in a command line in Bash (e.g. for the -t argument to sort), press ctrl-v [Tab] or write

$'\t'(the latter is better as you can copy/paste it). -

The standard tools for patching source code are

diffandpatch. See alsodiffstatfor summary statistics of a diff andsdifffor a side-by-side diff. Notediff -rworks for entire directories. Usediff -r tree1 tree2 | diffstatfor a summary of changes. Usevimdiffto compare and edit files. -

For binary files, use

hd,hexdumporxxdfor simple hex dumps andbviorbiewfor binary editing. -

Also for binary files,

strings(plusgrep, etc.) lets you find bits of text. -

For binary diffs (delta compression), use

xdelta3. -

To convert text encodings, try

iconv. Oruconvfor more advanced use; it supports some advanced Unicode things. For example, this command lowercases and removes all accents (by expanding and dropping them):

uconv -f utf-8 -t utf-8 -x '::Any-Lower; ::Any-NFD; [:Nonspacing Mark:] >; ::Any-NFC; ' < input.txt > output.txt

-

To split files into pieces, see

split(to split by size) andcsplit(to split by a pattern). -

To manipulate date and time expressions, use

dateadd,datediff,strptimeetc. fromdateutils. -

Use

zless,zmore,zcat, andzgrepto operate on compressed files. -

File attributes are settable via

chattrand offer a lower-level alternative to file permissions. For example, to protect against accidental file deletion the immutable flag:sudo chattr +i /critical/directory/or/file -

Use

getfaclandsetfaclto save and restore file permissions. For example:

getfacl -R /some/path > permissions.txt

setfacl --restore=permissions.txt

System debugging

-

For web debugging,

curlandcurl -Iare handy, or theirwgetequivalents, or the more modernhttpie. -

To know current cpu/disk status, the classic tools are

top(or the betterhtop),iostat, andiotop. Useiostat -mxz 15for basic CPU and detailed per-partition disk stats and performance insight. -

For network connection details, use

netstatandss. -

For a quick overview of what's happening on a system,

dstatis especially useful. For broadest overview with details, useglances. -

To know memory status, run and understand the output of

freeandvmstat. In particular, be aware the "cached" value is memory held by the Linux kernel as file cache, so effectively counts toward the "free" value. -

Java system debugging is a different kettle of fish, but a simple trick on Oracle's and some other JVMs is that you can run

kill -3 <pid>and a full stack trace and heap summary (including generational garbage collection details, which can be highly informative) will be dumped to stderr/logs. The JDK'sjps,jstat,jstack,jmapare useful. SJK tools are more advanced. -

Use

mtras a better traceroute, to identify network issues. -

For looking at why a disk is full,

ncdusaves time over the usual commands likedu -sh *. -

To find which socket or process is using bandwidth, try

iftopornethogs. -

The

abtool (comes with Apache) is helpful for quick-and-dirty checking of web server performance. For more complex load testing, trysiege. -

For more serious network debugging,

wireshark,tshark, orngrep. -

Know about

straceandltrace. These can be helpful if a program is failing, hanging, or crashing, and you don't know why, or if you want to get a general idea of performance. Note the profiling option (-c), and the ability to attach to a running process (-p). -

Know about

lddto check shared libraries etc. -

Know how to connect to a running process with

gdband get its stack traces. -

Use

/proc. It's amazingly helpful sometimes when debugging live problems. Examples:/proc/cpuinfo,/proc/meminfo,/proc/cmdline,/proc/xxx/cwd,/proc/xxx/exe,/proc/xxx/fd/,/proc/xxx/smaps(wherexxxis the process id or pid). -

When debugging why something went wrong in the past,

sarcan be very helpful. It shows historic statistics on CPU, memory, network, etc. -

For deeper systems and performance analyses, look at

stap(SystemTap),perf, andsysdig. -

Check what OS you're on with

unameoruname -a(general Unix/kernel info) orlsb_release -a(Linux distro info). -

Use

dmesgwhenever something's acting really funny (it could be hardware or driver issues). -

If you delete a file and it doesn't free up expected disk space as reported by

du, check whether the file is in use by a process:lsof | grep deleted | grep "filename-of-my-big-file"

One-liners

A few examples of piecing together commands:

- It is remarkably helpful sometimes that you can do set intersection, union, and difference of text files via

sort/uniq. Supposeaandbare text files that are already uniqued. This is fast, and works on files of arbitrary size, up to many gigabytes. (Sort is not limited by memory, though you may need to use the-Toption if/tmpis on a small root partition.) See also the note aboutLC_ALLabove andsort's-uoption (left out for clarity below).

cat a b | sort | uniq > c # c is a union b

cat a b | sort | uniq -d > c # c is a intersect b

cat a b b | sort | uniq -u > c # c is set difference a - b

-

Use

grep . *to quickly examine the contents of all files in a directory (so each line is paired with the filename), orhead -100 *(so each file has a heading). This can be useful for directories filled with config settings like those in/sys,/proc,/etc. -

Summing all numbers in the third column of a text file (this is probably 3X faster and 3X less code than equivalent Python):

awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }' myfile

- To see sizes/dates on a tree of files, this is like a recursive

ls -lbut is easier to read thanls -lR:

find . -type f -ls

- Say you have a text file, like a web server log, and a certain value that appears on some lines, such as an

acct_idparameter that is present in the URL. If you want a tally of how many requests for eachacct_id:

cat access.log | egrep -o 'acct_id=[0-9]+' | cut -d= -f2 | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

-

To continuously monitor changes, use

watch, e.g. check changes to files in a directory withwatch -d -n 2 'ls -rtlh | tail'or to network settings while troubleshooting your wifi settings withwatch -d -n 2 ifconfig. -

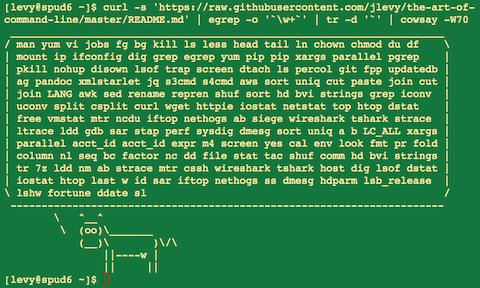

Run this function to get a random tip from this document (parses Markdown and extracts an item):

function taocl() {

curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jlevy/the-art-of-command-line/master/README.md |

pandoc -f markdown -t html |

xmlstarlet fo --html --dropdtd |

xmlstarlet sel -t -v "(html/body/ul/li[count(p)>0])[$RANDOM mod last()+1]" |

xmlstarlet unesc | fmt -80

}

Obscure but useful

-

expr: perform arithmetic or boolean operations or evaluate regular expressions -

m4: simple macro processor -

yes: print a string a lot -

cal: nice calendar -

env: run a command (useful in scripts) -

printenv: print out environment variables (useful in debugging and scripts) -

look: find English words (or lines in a file) beginning with a string -

cut,pasteandjoin: data manipulation -

fmt: format text paragraphs -

pr: format text into pages/columns -

fold: wrap lines of text -

column: format text fields into aligned, fixed-width columns or tables -

expandandunexpand: convert between tabs and spaces -

nl: add line numbers -

seq: print numbers -

bc: calculator -

factor: factor integers -

gpg: encrypt and sign files -

toe: table of terminfo entries -

nc: network debugging and data transfer -

socat: socket relay and tcp port forwarder (similar tonetcat) -

slurm: network traffic visualization -

dd: moving data between files or devices -

file: identify type of a file -

tree: display directories and subdirectories as a nesting tree; likelsbut recursive -

stat: file info -

time: execute and time a command -

timeout: execute a command for specified amount of time and stop the process when the specified amount of time completes. -

lockfile: create semaphore file that can only be removed byrm -f -

logrotate: rotate, compress and mail logs. -

watch: run a command repeatedly, showing results and/or highlighting changes -

tac: print files in reverse -

shuf: random selection of lines from a file -

comm: compare sorted files line by line -

pv: monitor the progress of data through a pipe -

hd,hexdump,xxd,biewandbvi: dump or edit binary files -

strings: extract text from binary files -

tr: character translation or manipulation -

iconvoruconv: conversion for text encodings -

splitandcsplit: splitting files -

sponge: read all input before writing it, useful for reading from then writing to the same file, e.g.,grep -v something some-file | sponge some-file -

units: unit conversions and calculations; converts furlongs per fortnight to twips per blink (see also/usr/share/units/definitions.units) -

apg: generates random passwords -

xz: high-ratio file compression -

ldd: dynamic library info -

nm: symbols from object files -

ab: benchmarking web servers -

strace: system call debugging -

mtr: better traceroute for network debugging -

cssh: visual concurrent shell -

rsync: sync files and folders over SSH or in local file system -

ngrep: grep for the network layer -

hostanddig: DNS lookups -

lsof: process file descriptor and socket info -

dstat: useful system stats -

glances: high level, multi-subsystem overview -

iostat: Disk usage stats -

mpstat: CPU usage stats -

vmstat: Memory usage stats -

htop: improved version of top -

last: login history -

w: who's logged on -

id: user/group identity info -

sar: historic system stats -

ss: socket statistics -

dmesg: boot and system error messages -

sysctl: view and configure Linux kernel parameters at run time -

hdparm: SATA/ATA disk manipulation/performance -

lsblk: list block devices: a tree view of your disks and disk partitions -

lshw,lscpu,lspci,lsusb,dmidecode: hardware information, including CPU, BIOS, RAID, graphics, devices, etc. -

lsmodandmodinfo: List and show details of kernel modules. -

fortune,ddate, andsl: um, well, it depends on whether you consider steam locomotives and Zippy quotations "useful"

OS X only

These are items relevant only on OS X.

-

Package management with

brew(Homebrew) and/orport(MacPorts). These can be used to install on OS X many of the above commands. -

Copy output of any command to a desktop app with

pbcopyand paste input from one withpbpaste. -

To enable the Option key in OS X Terminal as an alt key (such as used in the commands above like alt-b, alt-f, etc.), open Preferences -> Profiles -> Keyboard and select "Use Option as Meta key".

-

To open a file with a desktop app, use

openoropen -a /Applications/Whatever.app. -

Spotlight: Search files with

mdfindand list metadata (such as photo EXIF info) withmdls. -

Be aware OS X is based on BSD Unix, and many commands (for example

ps,ls,tail,awk,sed) have many subtle variations from Linux, which is largely influenced by System V-style Unix and GNU tools. You can often tell the difference by noting a man page has the heading "BSD General Commands Manual." In some cases GNU versions can be installed, too (such asgawkandgsedfor GNU awk and sed). If writing cross-platform Bash scripts, avoid such commands (for example, consider Python orperl) or test carefully. -

To get OS X release information, use

sw_vers.

Windows only

These items are relevant only on Windows.

-

On Windows 10, you can use Bash on Ubuntu on Windows, which provides a familiar Bash environment with Unix command line utilities. On the plus side, this allows Linux programs to run on Windows. On the other hand this does not support the running of Windows programs from the Bash prompt.

-

Access the power of the Unix shell under Microsoft Windows by installing Cygwin. Most of the things described in this document will work out of the box.

-

Install additional Unix programs with the Cygwin's package manager.

-

Use

minttyas your command-line window. -

Access the Windows clipboard through

/dev/clipboard. -

Run

cygstartto open an arbitrary file through its registered application. -

Access the Windows registry with

regtool. -

Note that a

C:\Windows drive path becomes/cygdrive/cunder Cygwin, and that Cygwin's/appears underC:\cygwinon Windows. Convert between Cygwin and Windows-style file paths withcygpath. This is most useful in scripts that invoke Windows programs. -

You can perform and script most Windows system administration tasks from the command line by learning and using

wmic. -

Another option to get Unix look and feel under Windows is Cash. Note that only very few Unix commands and command-line options are available in this environment.

-

An alternative option to get GNU developer tools (such as GCC) on Windows is MinGW and its MSYS package, which provides utilities such as bash, gawk, make and grep. MSYS doesn't have all the features compared to Cygwin. MinGW is particularly useful for creating native Windows ports of Unix tools.

More resources

- awesome-shell: A curated list of shell tools and resources.

- awesome-osx-command-line: A more in-depth guide for the OS X command line.

- Strict mode for writing better shell scripts.

- shellcheck: A shell script static analysis tool. Essentially, lint for bash/sh/zsh.

- Filenames and Pathnames in Shell: The sadly complex minutiae on how to handle filenames correctly in shell scripts.

- Data Science at the Command Line: More commands and tools helpful for doing data science, from the book of the same name

Disclaimer

With the exception of very small tasks, code is written so others can read it. With power comes responsibility. The fact you can do something in Bash doesn't necessarily mean you should! ;)

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.