28 KiB

[ Languages: English, Español, 한국어, Português, Русский, Slovenščina, 中文, German ]

The Art of Command Line

- Kurzbeschreibung

- Grundlagen

- Täglicher Gebrauch

- Umgang mit Dateien und Daten

- Fehlerbehebung auf Systemebene

- Einzeiler

- Eigenartig aber hilfreich

- Nur MacOS X

- Weitere Quellen

- Haftungsausschluss

Der flüssige Umgang mit der Kommandozeile ist eine oft vernachlässigte oder als undurchsichtig empfundene Fähigkeit, steigert jedoch Flexibilität und Produktivität eines Informatikers auf offensichtliche als auch subtile Weise. Was folgt, ist eine Auswahl an Notizen und Tipps im Umgang mit der Kommandozeile, welche ich beim Arbeiten mit Linux zu schätzen gelernt habe. Manche dieser Hinweise beinhalten Grundwissen, andere sind sehr spezifisch, fortgeschritten oder auch eigenartig. Die Seite ist nicht lang, aber wenn du alle Punkte verstanden hast und anwenden kannst, weißt du eine ganze Menge.

Vieles davon erschien ursprünglich auf Quora, aber angesichts des Interesses scheint es vielversprechend, Github zu nutzen, wo talentiertere Menschen als ich es bin kontinuierlich Verbesserungen vorschlagen können. Wenn du einen Fehler entdeckst oder etwas, das man besser machen könnte, erstelle ein Issue oder einen PR! (Lies aber bitte zuerst die Kurzbeschreibung und überprüfe bereits vorhandene Issues/PRs.)

Kurzbeschreibung

Umfang:

- Diese Anleitung richtet sich an Anfänger und Fortgeschrittene. Die Ziele sind The goals are Breite (alles ist wichtig), Genauigkeit (konkrete Beispiele für die gebräuchlichsten Anwendungsfälle) und Knappheit (Dinge, die nicht wesentlich sind oder leicht anderswo nachgeschlagen werden können, sollen vermieden werden). Jeder Tipp ist in einer bestimmten Situation wesentlich oder deutlich zeitsparend gegenüber bestehenden Alternativen.

- Sie ist für Linux geschrieben, mit der Ausnahme des Abschnitts "Nur MacOS X". Viele der anderen Punkte lassen sich nutzen oder sind installierbar auf anderen Unices oder MacOS (oder sogar Cygwin).

- Der Fokus liegt auf interaktiver Bash, allerdings gelten viele Tipps auch auf anderen Shells sowie für allgemeines Bash-Skripting.

- Sie beinhaltet sowohl "normale" Unix-Befehle als auch solche, die bestimmte installierte Pakete voaussetzen -- sofern sie wichtig genug sind, dass sie die Aufnahme in diese Anleitung verdienen.

Hinweise:

- Um eine Seite nicht zu sprengen, ist ihr Inhalt durchgängig anhand von Verweisen aufgelistet. Du bist schlau genug, anderswo zusätzliche Informationen nachzuschlagen, sobald du die Idee bzw. den Befehl dahinter kennst. Verwende

apt-get/yum/dnf/pacman/pip/brew(je nachdem), um neue Programme zu installieren. - Verwende Explainshell, um einen hilfreichen Einblick zu erhalten, was es mit Befehlen, Optionen, Pipes etc. auf sich hat.

Grundlagen

-

Lerne einfache Bash. Tatsächlich, gib

man bashein und überfliege das Ganze zumindest; es ist leicht zu verstehen und nicht allzu lang. Alternative Shells sind nett, aber Bash ist mächtig und immer verfügbar (nur zsh, fish, etc. zu lernen ist auf dem eigenen Laptop vielleicht reizvoll, beschränkt jedoch deine Möglichkeiten in vielerlei Hinsicht, etwa beim Arbeiten mit bestehenden Servern). -

Lerne mindestens einen Text-basierten Editor zu benutzen. Idealerweise Vim (

vi), da es letztlich keinen vergleichbaren Mitbewerber für gelegentliche Einsätze in einem Terminal gibt (selbst dann, wenn man eine große Entwicklungsumgebung wie Emacs oder die meiste Zeit einen modernen Hipster-Editor benutzt). -

Wisse, wie man Dokumentationen mit

manliest (für Neugierige,man manlistet Abschnittsnummern, bspw. stehen unter 1 "reguläre" Befehle, 5 beinhaltet Dateien/Konventionen und unter 8 solche zur Rechnerverwaltung). Finde man-Seiten mitapropos. Wisse, dass manche Befehle keine ausführbaren Dateien, sondern Bash-Builtins sind, und dass du Hilfe zu diesen mithelpundhelp -derhälst. -

Lerne etwas über die Umleitung von Ein- und Ausgaben per

>und<sowie|für Pipes. Wisse, dass>die Ausgabedatei überschreibt und>>etwas anhängt. Lerne etwas über stdout und stderr. -

Lerne etwas über die Dateinamenerweiterung mittels

*(und eventuell?und{...}) sowie Anführungszeichen, etwa den Unterschied zwischen doppelten"und einfachen'. (Mehr zur Variablenerweiterung findest du unten.) -

Mach dich vertraut mit Bash-Jobmanagement:

&, ctrl-z, ctrl-c,jobs,fg,bg,kill, etc. -

Kenne

sshund die Grundlagen passwortloser Authentifizierung mittelsssh-agent,ssh-add, etc. -

Grundlegende Dateiverwaltung:

lsandls -l(und spezieller, lerne die Funktion jeder einzelnen Spalte vonls -lkennen),less,head,tailundtail -f(oder noch besser,less +F),lnundln -s(lerne die Unterschiede und Vorteile von Hard- und Softlinks),chown,chmod,du(für eine Kurzzusammenfassung der Festplattenbelegung:du -hs *). Für Dateisystemmanagement,df,mount,fdisk,mkfs,lsblk. -

Grundlagen der Netzwerkverwaltung:

ipoderifconfig,dig. -

Kenne reguläre Ausdrücke gut, und die verschiedenen Statusindikatoren zu

grep/egrep. Die Optionen-i,-o,-v,-A,-B, und-Csind gut zu wissen. -

Lerne den Umgang mit

apt-get,yum,dnfoderpacman(je nach Distribution), um Pakete zu finden bzw. zu installieren. Und stell sicher, dass dupiphast, um Python-basierte Kommandozeilen-Tools nutzen zu können (einige der untenstehenden werden am einfachsten überpipinstalliert).

Täglicher Gebrauch

-

In Bash kannst du mit Tab Parameter vervollständigen und mit ctrl-r bereits benutzte Befehle durchsuchen.

-

In Bash kannst du mit ctrl-w das letzte Wort löschen und mit ctrl-u alles bis zum Anfang einer Zeile. Verwende alt-b und alt-f, um dich Wort für Wort fortzubewegen, springe mit ctrl-a zum Beginn einer Zeile, mit ctrl-e zum Ende einer Zeile, lösche mit ctrl-k alles bis zum Ende einer Zeile und bereinige mit ctrl-l den Bildschirm. Siehe

man readlinefür alle voreingestellten Tastenbelegungen in Bash. Davon gibt's viele. Zum Beispiel alt-. wechselt durch vorherige Parameter und alt-* erweitert ein Suchmuster. -

Alternativ, falls du vi-artige Tastenbelegungen magst, verwende

set -o vi. -

Um kürzich genutzte Befehle zu sehen,

history. Es gibt außerdem viele Abkürzungen wie etwa!$(letzter Parameter) und!!(letzter Befehl), wenngleich diese oft einfach ersetzt werden durch ctrl-r und alt-.. -

Um ins vorangegangene Arbeitsverzeichnis zu gelangen:

cd - -

If you are halfway through typing a command but change your mind, hit alt-# to add a

#at the beginning and enter it as a comment (or use ctrl-a, #, enter). You can then return to it later via command history. -

Verwende

xargs(oderparallel). Es ist sehr mächtig. Beachte, wie du viele Dinge pro Zeile (-L) als auch parallel (-P) ausführen kannst. Wenn du dir nicht sicher bist, ob das Richtige dabei herauskommt, verwende zunächstxargs echo. Außerdem ist-I{}nützlich. Beispiele:

find . -name '*.py' | xargs grep irgendeine_funktion

cat hosts | xargs -I{} ssh root@{} hostname

-

pstree -pliefert eine hilfreiche Anzeige des Prozessbaums. -

Verwende

pgrepundpkill, um Prozesse anhand eines Namens zu finden oder festzustellen (-fist hilfreich). -

Kenne die verschiedenen Signale, die du Prozessen senden kannst. Um einen Prozess etwa zu unterbrechen, verwende

kill -STOP [pid]. Für die vollständige Liste, sieheman 7 signal -

Verwende

nohupoderdisown, wenn du einen Hintergrundprozess für immer laufen lassen willst. -

Überprüfe mithörende Prozesse mit

netstat -lntpoderss -plat(für TCP; füge-ufür UDP hinzu). -

Siehe zudem

lsoffür offene Sockets und Dateien. -

Siehe

uptimeoderw, um die laufende Betriebszeit des Systems zu erfahren, -

Verwende

alias, um Verknüpfungen für gebräuchliche Befehle zu erstellen. So erstellt etwaalias ll='ls -latr'den neuen Aliasll. -

Verwende in Bash-Skripts

set -xzur Fehlerbehebung. Benutze strict modes wann immer möglich. Verwendeset -ezum Abbruch bei Fehlern. Benutzeset -o pipefailebenfalls, um mit Fehlern präzise zu arbeiten (auch wenn dieses Thema etwas heikel ist). Verwende für etwas komplexere Skripte weiterhintrap. -

In Bash-Skripts stellen Subshells (geschrieben in runden Klammern) einen praktischen Weg dar, Befehle zusammenzufassen. Ein gebräuchliches Beispiel ist die vorübergehende Arbeit in einem anderen Arbeitsverzeichnis:

# erledige etwas im aktuellen Verzeichnis

(cd /irgendein/anderes/verzeichnis && anderer-befehl)

# fahre fort im aktuellen Verzeichnis

-

Beachte, dass es in Bash viele Möglichkeiten gibt, Variablen zu erweitern. Überprüfen, ob eine Variable existiert:

${name:?error message}.Wenn bspw. ein Bash-Skript nur einen einzelnen Parameter benötigt, schreibe einfachinput_file=${1:?usage: $0 input_file}. Arithmetische Erweiterung:i=$(( (i + 1) % 5 )). Sequenzen:{1..10}. Zeichenkette kürzen:${var%suffix}und${var#prefix}. Wenn bspw.var=foo.pdf, dann gibtecho ${var%.pdf}.txtdie Ausgabefoo.txtaus. -

Die Ausgabe eines Befehls kann wie eine Datei behandelt werden mit

<(irgendein befehl). Das Vergleichen der lokalen/etc/hostsmit einer entfernten:

diff /etc/hosts <(ssh andererhost cat /etc/hosts)

-

Kenne "here documents" in Bash, wie etwa in

cat <<EOF .... -

In Bash,leite sowohl den standard output als auch den standard error um mit:

irgendein-befehl >logfile 2>&1. Oftmals ist es gute Praxis, einen Befehl an das verwendete Terminal zu binden, um keinen offenen Dateizugriff im standard input zu erzeugen, also</dev/nullhinzuzufügen. -

Verwende

man asciifür eine gute ASCII-Tabelle, Mit Dezimal- und Hexadezimalwerten. Für allgemeine Informationen zu Kodierung sindman unicode,man utf-8undman latin1hilfreich. -

Verwende

screenodertmux, um einen Bildschirm zu multiplexen, besonders hilfreich ist dies für Fernzugriffe per ssh und zur Trennung und Neuverbindung mit einer Session. Eine minimalistische Alternative allein zur Aufrechterhaltung einer Session istdtach. -

Bei SSH ist es hilfreich zu wissen, wie man einen Porttunnel mit

-Loder-D(gelegentlich auch-R) einrichtet, etwa beim Zugriff auf Webseiten von einem Remote-Server. -

Es kann nützlich sein, ein paar Verbesserungen an den SSH-Einstellungen vorzunehmen; so enthält bspw. diese

~/.ssh/configEinstellungen, um das Abreißen der Verbindung in bestimmten Netzwerkumgebungen zu vermeiden, verwendet Kompression (was hilfreich ist bei SCP über Verbindungen mit niedriger Bandbreite) und Multiplex-Kanäle zu demselben Server mithilfe einer lokalen Kontrolldatei:

TCPKeepAlive=yes

ServerAliveInterval=15

ServerAliveCountMax=6

Compression=yes

ControlMaster auto

ControlPath /tmp/%r@%h:%p

ControlPersist yes

-

Einige andere Optionen im Zusammenhang mit SSH sind sicherheitsrelevant und sollten nur mit Bedacht aktiviert werden, etwa Zugriff per Subnet oder Host sowie in vertrauenswürdigen Netzwerken:

StrictHostKeyChecking=no,ForwardAgent=yes -

Um Zugriff auf eine Datei in Oktalform zu erhalten, was zur Systemkonfiguration zwar nützlich, jedoch über

lsnicht verfügbar und leicht zu vermasseln ist, verwende etwas wie

stat -c '%A %a %n' /etc/timezone

-

Verwende zur interaktiven Auswahl von Werten aus dem Output eines anderen Befehls

percoloderfzf. -

Verwende

fpp(PathPicker) zur Interaktion mit Dateien als Output eines anderen Befehls (wie etwagit). -

Verwende für einen einfachen Webserver für alle Dateien im aktuellen Verzeichnis (sowie Unterverzeichnisse), der für alle in deinem Netzwerk abrufbar ist:

python -m SimpleHTTPServer 7777(für Port 7777 und Python 2) sowiepython -m http.server 7777(für Port 7777 und Python 3). -

Um einen Befehl mit Privilegien zu nutzen, verwende

sudo(für root) odersudo -u(für einen anderen Benutzer). Verwendesuodersudo bash, um eine Shell als eben dieser Benutzer auszuführen. Verwendesu -zur Simulierung einer frischen Anmeldung als root oder anderer Benutzer.

Umgang mit Dateien und Daten

-

To locate a file by name in the current directory,

find . -iname '*something*'(or similar). To find a file anywhere by name, uselocate something(but bear in mindupdatedbmay not have indexed recently created files). -

For general searching through source or data files (more advanced than

grep -r), useag. -

To convert HTML to text:

lynx -dump -stdin -

For Markdown, HTML, and all kinds of document conversion, try

pandoc. -

If you must handle XML,

xmlstarletis old but good. -

For JSON, use

jq. -

For Excel or CSV files, csvkit provides

in2csv,csvcut,csvjoin,csvgrep, etc. -

For Amazon S3,

s3cmdis convenient ands4cmdis faster. Amazon'sawsis essential for other AWS-related tasks. -

Know about

sortanduniq, including uniq's-uand-doptions -- see one-liners below. See alsocomm. -

Know about

cut,paste, andjointo manipulate text files. Many people usecutbut forget aboutjoin. -

Know about

wcto count newlines (-l), characters (-m), words (-w) and bytes (-c). -

Know about

teeto copy from stdin to a file and also to stdout, as inls -al | tee file.txt. -

Know that locale affects a lot of command line tools in subtle ways, including sorting order (collation) and performance. Most Linux installations will set

LANGor other locale variables to a local setting like US English. But be aware sorting will change if you change locale. And know i18n routines can make sort or other commands run many times slower. In some situations (such as the set operations or uniqueness operations below) you can safely ignore slow i18n routines entirely and use traditional byte-based sort order, usingexport LC_ALL=C. -

Know basic

awkandsedfor simple data munging. For example, summing all numbers in the third column of a text file:awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }'. This is probably 3X faster and 3X shorter than equivalent Python. -

To replace all occurrences of a string in place, in one or more files:

perl -pi.bak -e 's/old-string/new-string/g' my-files-*.txt

- To rename many files at once according to a pattern, use

rename. For complex renames,reprenmay help.

# Recover backup files foo.bak -> foo:

rename 's/\.bak$//' *.bak

# Full rename of filenames, directories, and contents foo -> bar:

repren --full --preserve-case --from foo --to bar .

-

Use

shufto shuffle or select random lines from a file. -

Know

sort's options. For numbers, use-n, or-hfor handling human-readable numbers (e.g. fromdu -h). Know how keys work (-tand-k). In particular, watch out that you need to write-k1,1to sort by only the first field;-k1means sort according to the whole line. Stable sort (sort -s) can be useful. For example, to sort first by field 2, then secondarily by field 1, you can usesort -k1,1 | sort -s -k2,2. -

If you ever need to write a tab literal in a command line in Bash (e.g. for the -t argument to sort), press ctrl-v [Tab] or write

$'\t'(the latter is better as you can copy/paste it). -

The standard tools for patching source code are

diffandpatch. See alsodiffstatfor summary statistics of a diff. Notediff -rworks for entire directories. Usediff -r tree1 tree2 | diffstatfor a summary of changes. -

For binary files, use

hdfor simple hex dumps andbvifor binary editing. -

Also for binary files,

strings(plusgrep, etc.) lets you find bits of text. -

For binary diffs (delta compression), use

xdelta3. -

To convert text encodings, try

iconv. Oruconvfor more advanced use; it supports some advanced Unicode things. For example, this command lowercases and removes all accents (by expanding and dropping them):

uconv -f utf-8 -t utf-8 -x '::Any-Lower; ::Any-NFD; [:Nonspacing Mark:] >; ::Any-NFC; ' < input.txt > output.txt

-

To split files into pieces, see

split(to split by size) andcsplit(to split by a pattern). -

Use

zless,zmore,zcat, andzgrepto operate on compressed files.

System debugging

-

For web debugging,

curlandcurl -Iare handy, or theirwgetequivalents, or the more modernhttpie. -

To know disk/cpu/network status, use

iostat,netstat,top(or the betterhtop), and (especially)dstat. Good for getting a quick idea of what's happening on a system. -

For a more in-depth system overview, use

glances. It presents you with several system level statistics in one terminal window. Very helpful for quickly checking on various subsystems. -

To know memory status, run and understand the output of

freeandvmstat. In particular, be aware the "cached" value is memory held by the Linux kernel as file cache, so effectively counts toward the "free" value. -

Java system debugging is a different kettle of fish, but a simple trick on Oracle's and some other JVMs is that you can run

kill -3 <pid>and a full stack trace and heap summary (including generational garbage collection details, which can be highly informative) will be dumped to stderr/logs. The JDK'sjps,jstat,jstack,jmapare useful. SJK tools are more advanced. -

Use

mtras a better traceroute, to identify network issues. -

For looking at why a disk is full,

ncdusaves time over the usual commands likedu -sh *. -

To find which socket or process is using bandwidth, try

iftopornethogs. -

The

abtool (comes with Apache) is helpful for quick-and-dirty checking of web server performance. For more complex load testing, trysiege. -

For more serious network debugging,

wireshark,tshark, orngrep. -

Know about

straceandltrace. These can be helpful if a program is failing, hanging, or crashing, and you don't know why, or if you want to get a general idea of performance. Note the profiling option (-c), and the ability to attach to a running process (-p). -

Know about

lddto check shared libraries etc. -

Know how to connect to a running process with

gdband get its stack traces. -

Use

/proc. It's amazingly helpful sometimes when debugging live problems. Examples:/proc/cpuinfo,/proc/meminfo,/proc/cmdline,/proc/xxx/cwd,/proc/xxx/exe,/proc/xxx/fd/,/proc/xxx/smaps(wherexxxis the process id or pid). -

When debugging why something went wrong in the past,

sarcan be very helpful. It shows historic statistics on CPU, memory, network, etc. -

For deeper systems and performance analyses, look at

stap(SystemTap),perf, andsysdig. -

Check what OS you're on with

unameoruname -a(general Unix/kernel info) orlsb_release -a(Linux distro info). -

Use

dmesgwhenever something's acting really funny (it could be hardware or driver issues).

One-liners

A few examples of piecing together commands:

- It is remarkably helpful sometimes that you can do set intersection, union, and difference of text files via

sort/uniq. Supposeaandbare text files that are already uniqued. This is fast, and works on files of arbitrary size, up to many gigabytes. (Sort is not limited by memory, though you may need to use the-Toption if/tmpis on a small root partition.) See also the note aboutLC_ALLabove andsort's-uoption (left out for clarity below).

cat a b | sort | uniq > c # c is a union b

cat a b | sort | uniq -d > c # c is a intersect b

cat a b b | sort | uniq -u > c # c is set difference a - b

-

Use

grep . *to visually examine all contents of all files in a directory, e.g. for directories filled with config settings, like/sys,/proc,/etc. -

Summing all numbers in the third column of a text file (this is probably 3X faster and 3X less code than equivalent Python):

awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }' myfile

- If want to see sizes/dates on a tree of files, this is like a recursive

ls -lbut is easier to read thanls -lR:

find . -type f -ls

- Say you have a text file, like a web server log, and a certain value that appears on some lines, such as an

acct_idparameter that is present in the URL. If you want a tally of how many requests for eachacct_id:

cat access.log | egrep -o 'acct_id=[0-9]+' | cut -d= -f2 | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

-

To continuously monitor changes, use

watch, e.g. check changes to files in a directory withwatch -d -n 2 'ls -rtlh | tail'or to network settings while troubleshooting your wifi settings withwatch -d -n 2 ifconfig. -

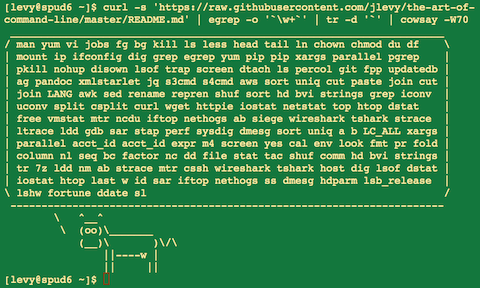

Run this function to get a random tip from this document (parses Markdown and extracts an item):

function taocl() {

curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jlevy/the-art-of-command-line/master/README.md |

pandoc -f markdown -t html |

xmlstarlet fo --html --dropdtd |

xmlstarlet sel -t -v "(html/body/ul/li[count(p)>0])[$RANDOM mod last()+1]" |

xmlstarlet unesc | fmt -80

}

Obscure but useful

-

expr: perform arithmetic or boolean operations or evaluate regular expressions -

m4: simple macro processor -

yes: print a string a lot -

cal: nice calendar -

env: run a command (useful in scripts) -

printenv: print out environment variables (useful in debugging and scripts) -

look: find English words (or lines in a file) beginning with a string -

cut,pasteandjoin: data manipulation -

fmt: format text paragraphs -

pr: format text into pages/columns -

fold: wrap lines of text -

column: format text fields into aligned, fixed-width columns or tables -

expandandunexpand: convert between tabs and spaces -

nl: add line numbers -

seq: print numbers -

bc: calculator -

factor: factor integers -

gpg: encrypt and sign files -

toe: table of terminfo entries -

nc: network debugging and data transfer -

socat: socket relay and tcp port forwarder (similar tonetcat) -

slurm: network trafic visualization -

dd: moving data between files or devices -

file: identify type of a file -

tree: display directories and subdirectories as a nesting tree; likelsbut recursive -

stat: file info -

time: execute and time a command -

watch: run a command repeatedly, showing results and/or highlighting changes -

tac: print files in reverse -

shuf: random selection of lines from a file -

comm: compare sorted files line by line -

pv: monitor the progress of data through a pipe -

hdandbvi: dump or edit binary files -

strings: extract text from binary files -

tr: character translation or manipulation -

iconvoruconv: conversion for text encodings -

splitandcsplit: splitting files -

sponge: read all input before writing it, useful for reading from then writing to the same file, e.g.,grep -v something some-file | sponge some-file -

units: unit conversions and calculations; converts furlongs per fortnight to twips per blink (see also/usr/share/units/definitions.units) -

7z: high-ratio file compression -

ldd: dynamic library info -

nm: symbols from object files -

ab: benchmarking web servers -

strace: system call debugging -

mtr: better traceroute for network debugging -

cssh: visual concurrent shell -

rsync: sync files and folders over SSH or in local file system -

wiresharkandtshark: packet capture and network debugging -

ngrep: grep for the network layer -

hostanddig: DNS lookups -

lsof: process file descriptor and socket info -

dstat: useful system stats -

glances: high level, multi-subsystem overview -

iostat: Disk usage stats -

mpstat: CPU usage stats -

vmstat: Memory usage stats -

htop: improved version of top -

last: login history -

w: who's logged on -

id: user/group identity info -

sar: historic system stats -

iftopornethogs: network utilization by socket or process -

ss: socket statistics -

dmesg: boot and system error messages -

sysctl: view and configure Linux kernel parameters at run time -

hdparm: SATA/ATA disk manipulation/performance -

lsb_release: Linux distribution info -

lsblk: list block devices: a tree view of your disks and disk paritions -

lshw,lscpu,lspci,lsusb,dmidecode: hardware information, including CPU, BIOS, RAID, graphics, devices, etc. -

lsmodandmodifno: List and show details of kernel modules. -

fortune,ddate, andsl: um, well, it depends on whether you consider steam locomotives and Zippy quotations "useful"

MacOS X only

These are items relevant only on MacOS.

-

Package management with

brew(Homebrew) and/orport(MacPorts). These can be used to install on MacOS many of the above commands. -

Copy output of any command to a desktop app with

pbcopyand paste input from one withpbpaste. -

To enable the Option key in Mac OS Terminal as an alt key (such as used in the commands above like alt-b, alt-f, etc.), open Preferences -> Profiles -> Keyboard and select "Use Option as Meta key".

-

To open a file with a desktop app, use

openoropen -a /Applications/Whatever.app. -

Spotlight: Search files with

mdfindand list metadata (such as photo EXIF info) withmdls. -

Be aware MacOS is based on BSD Unix, and many commands (for example

ps,ls,tail,awk,sed) have many subtle variations from Linux, which is largely influenced by System V-style Unix and GNU tools. You can often tell the difference by noting a man page has the heading "BSD General Commands Manual." In some cases GNU versions can be installed, too (such asgawkandgsedfor GNU awk and sed). If writing cross-platform Bash scripts, avoid such commands (for example, consider Python orperl) or test carefully.

More resources

- awesome-shell: A curated list of shell tools and resources.

- Strict mode for writing better shell scripts.

- shellcheck - A shell script static analysis tool. Essentially, lint for bash/sh/zsh.

Disclaimer

With the exception of very small tasks, code is written so others can read it. With power comes responsibility. The fact you can do something in Bash doesn't necessarily mean you should! ;)

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.