25 KiB

[ Languages: 中文 ]

The Art of Command Line

- Meta

- Basics

- Everyday use

- Processing files and data

- System debugging

- One-liners

- Obscure but useful

- More resources

- Disclaimer

Fluência na linha de comando é uma skill muitas vezes negligenciada ou considerada obsoleta, porém ela aumenta sua flexibilidade e produtividade como um desenvolvedor. Este texto descreve uma selação de notas e dicas de uso da linha de comando que eu tenho encontrado muita utilidade usando o Linux. Algumas dicas são elementares, e algumas são mais específicas, sofisticadas ou obscuras. Esta página não é tão longa, mas se você puder usar e relembrar todos os items que estão aqui, então você possui tem bastante conhecimento.

Mais sobre isso originalmente apareceu no Quora, mas dado o interesse lá, então parece que é importante usar o Github, onde pessoas mais talentosas do que eu, prontamente podem sugerir melhorias. Se você ver um erro ou algo que poderia ser melhorado, por favor abra uma issue ou um PR! (E claro por favor revise as meta sections e PRs/issues existentes primeiro.)

Meta

Escopo:

- Este guia é destinado tanto para iniciantes como para usuários mais experientes. Os objetivos são breadth (tudo de importante), aprofundamento (dar exemplos concretos dos casos de uso mais comuns), e brevidade (evitar coisas que não são tão essenciais or digressões que vou pode facilmente encontrar por aí). Todas as dicas são essenciais em alguma situação ou trazem uma economia notável de tempo em relação a outras alternativas.

- Este guia é escrito para o Linux. Muitos, mas não todos os items se aplicam igualmente para o MacOS (ou mesmo o Cygwin).

- O foco está na interatividade no Bash, embora muitas dicas aqui são aplicadas para outros shells e em geral para Bash script.

- Este inclui tanto comandos Unix "padrão", como comandos que requerem instalação de pacotes adicionais -- tanto quanto estes sejam importantes o suficiente para merecerem sua inclusão.

Notas:

- Para manter este guia em uma página, o conteúdo implícito será incluído por referência. Você é experto o suficiente para verificar mais detalhes em outros lugares, uma vez que você já tenha entendido a ideia ou siga para o Google. Use

apt-get/yum/dnf/pacman/pip/brew(como adequado) para instalar novos programas. - Use Explainshell para encontrar informações úteis sobre comandos, opções, pipes e etc. faz.

Básico

-

Aprenda o básico sobre Bash. Atualmente, digite

man bashe pelo menos entenda superficialmente o seu funcionamento; é bastante de ler e nem é tão grande assim. Shells alternativos podem serem legais, mas o Bash é mais poderoso e sempre estar disponível (aprendendo somente zsh, fish, etc, é enquanto tentador no seu próprio notebook, restringe você em muitas situações, como ao usar servidores existentes). -

Aprenda pelo menos um editor text-base bem. Idealmente o Vim (

vi), como não existe nenhuma competição aleatória de edição em um terminal ( mesmo se você usa o Emacs, uma grande IDE, ou um moderno editor hipster a maioria do tempo). -

Saiba como ler a documentação com o

man(por curiosidade,man manlista os números das seções, exemplo. 1 se refere aos comandos "regular", 5 é sobre arquivos/convenções, e 8 se diz respeito a administração). Procure outras documentos do man com oapropos. Saiba que alguns dos comandos não são executáveis, mas sim builins(embutidos) no bash, os quais você poderá conseguir ajuda comhelpehelp -d. -

Aprenda a respeito do redirecionamento da saída e entrada usando

>e<e pipes usando|. Aprenda sobre o stdout e stdin. -

Aprenda sobre a expensão de arquivos glob com

*( e talvez?e{...}) and quoting and the difference entre aspas duplas"e aspas simples'. (Veja mais em expansões de variáveis abaixo.) -

Esteja familiar com o gerenciamento de jobs no Bash:

&, ctrl-z, ctrl-c,jobs,fg,bg,kill, etc. -

Aprenda

ssh, e o básico de autenticação sem senha, através dossh-agent,ssh-add, etc. -

Gerenciamento básico de arquivos:

lsels -l(em particular, aprenda o que cada coluna significa nols -lsignifica),less,head,tailandtail -f(ou ainda melhor,less +F),lneln -s(aprenda as diferenças e vantagens de soft links versus hard links),chown,chmod,du(para um rápido resumo do uso do disco:du -sk *). Para gerenciamento do sistema de arquivos,df,mount,fdisk,mkfs,lsblk. -

Gerenciamento básico da rede:

ipouifconfig,dig. -

Sabia bem expressões regulares, e as várias flags para

grep/egrep. As-i,-o,-A, e-Bsão opções que é importante saber. -

Aprenda a usar

apt-get,yum,dnfoupacman(dependendo da distribuição) para procurar e instalar pacotes. E garanta que você possui opippara instalar ferramentas baseadas em Python (algumas abaixo são fáceis de instalar através dopip).

Uso diário

-

No Bash, use Tab para completar argumentos e ctrl-r para pesquisar através do histórico de comandos.

-

No Bash, utilize ctrl-w para deletar a última palavra, e ctrl-u para deletar tudo e voltar para o início da linha. Use alt-b e alt-f para se mover por palavras, ctrl-k para apagar até o final da linha, ctrl-l para limpar a tela. Consulte

man readlinepara todos os keybindings padrões do Bash. Existem muitos. Por exemplo alt-. circula através dos argumentos anteriores, e alt-* expande um glob. *** -

Como alternativa, se você ama os keybinds ao estilo do vi, use

set -o vi. -

Para ver os comandos recentes,

history. Existem também muitas abreviações como!$(último argumento) e!!último comando, embora estes sejam muitas vezes facilmente substituídos por ctrl-r e alt-.. -

Volte atrás para o diretório de trabalho anterior:

cd -. -

Se você estar na metade do caminho ao digitar um comando, mas mudou de ideia, tecle alt-# para adicionar um

#ao início e defina este como um comentário (ou use ctrl-a. #. enter). Você pode então recuperar o comando mais tarde através do histórico de comandos. -

Use

xargs(ouparallel). Estes são muito poderosos. Note que você pode controlar como os vários items são executados por linha (-L) assim como o paralelismo (-P). Se você não tem certeza de isto é a coisa certa a se fazer, usexargs echoprimeiro. O-I{}também é muito útil. Exemplos:

find . -name '*.py' | xargs grep some_function

cat hosts | xargs -I{} ssh root@{} hostname

-

pstree -pé um modo de visualização muito útil da árvore de processos. -

Use

pgrepepkillpara procurar ou sinalizar os processo pelo seu nome (-fé muito útil). -

Saiba os vários sinais que você pode enviar para um processo. Por exemplo, para suspender um processo, use

kill -STOP [pid]. Para saber a lista completas dos sinais, vejaman 7 signal. -

Use

nohupoudisownse você deseja por o processo em background executando para sempre. -

Verifique quais processos estão escutando através

netstat -lntpouss -plat(para TCP; adicione-upara UDP). -

Veja também

lsofpara abrir sockets e arquivos. -

Em scripts Bash, use

set -xpara debugar a saída. Utilize modos estritos sempre que for possível. Useset -epara abortar em caso de erros. Useset -o pipefailcomo também, para ser restrito a respeito dos erros (embora este tópico seja um pouco sútil). Para scripts mais desenvolvidos, use tambémtrap. -

Em Bash scripts, subshells (escrito com parênteses) são formas convenientes de agrupar comandos. Um exemplo comum é temporariamente mover para um diretório de trabalho diferente, e.g.

# faz algo no diretório corrente

(cd /some/other/dir && other-command)

# continua no diretório atual

-

In Bash, note there are lots of kinds of variable expansion. Checking a variable exists:

${name:?error message}. For example, if a Bash script requires a single argument, just writeinput_file=${1:?usage: $0 input_file}. Arithmetic expansion:i=$(( (i + 1) % 5 )). Sequences:{1..10}. Trimming of strings:${var%suffix}and${var#prefix}. For example ifvar=foo.pdf, thenecho ${var%.pdf}.txtprintsfoo.txt. -

The output of a command can be treated like a file via

<(some command). For example, compare local/etc/hostswith a remote one:

diff /etc/hosts <(ssh somehost cat /etc/hosts)

-

Know about "here documents" in Bash, as in

cat <<EOF .... -

In Bash, redirect both standard output and standard error via:

some-command >logfile 2>&1. Often, to ensure a command does not leave an open file handle to standard input, tying it to the terminal you are in, it is also good practice to add</dev/null. -

Use

man asciifor a good ASCII table, with hex and decimal values. For general encoding info,man unicode,man utf-8, andman latin1are helpful. -

Use

screenortmuxto multiplex the screen, especially useful on remote ssh sessions and to detach and re-attach to a session. A more minimal alternative for session persistence only isdtach. -

In ssh, knowing how to port tunnel with

-Lor-D(and occasionally-R) is useful, e.g. to access web sites from a remote server. -

It can be useful to make a few optimizations to your ssh configuration; for example, this

~/.ssh/configcontains settings to avoid dropped connections in certain network environments, use compression (which is helpful with scp over low-bandwidth connections), and multiplex channels to the same server with a local control file:

TCPKeepAlive=yes

ServerAliveInterval=15

ServerAliveCountMax=6

Compression=yes

ControlMaster auto

ControlPath /tmp/%r@%h:%p

ControlPersist yes

-

A few other options relevant to ssh are security sensitive and should be enabled with care, e.g. per subnet or host or in trusted networks:

StrictHostKeyChecking=no,ForwardAgent=yes -

To get the permissions on a file in octal form, which is useful for system configuration but not available in

lsand easy to bungle, use something like

stat -c '%A %a %n' /etc/timezone

-

For interactive selection of values from the output of another command, use

percol. -

For interaction with files based on the output of another command (like

git), usefpp(PathPicker). -

For a simple web server for all files in the current directory (and subdirs), available to anyone on your network, use:

python -m SimpleHTTPServer 7777(for port 7777 and Python 2) andpython -m http.server 7777(for port 7777 and Python 3).

Processing files and data

-

To locate a file by name in the current directory,

find . -iname '*something*'(or similar). To find a file anywhere by name, uselocate something(but bear in mindupdatedbmay not have indexed recently created files). -

For general searching through source or data files (more advanced than

grep -r), useag. -

To convert HTML to text:

lynx -dump -stdin -

For Markdown, HTML, and all kinds of document conversion, try

pandoc. -

If you must handle XML,

xmlstarletis old but good. -

For JSON, use

jq. -

For Excel or CSV files, csvkit provides

in2csv,csvcut,csvjoin,csvgrep, etc. -

For Amazon S3,

s3cmdis convenient ands4cmdis faster. Amazon'sawsis essential for other AWS-related tasks. -

Know about

sortanduniq, including uniq's-uand-doptions -- see one-liners below. See alsocomm. -

Know about

cut,paste, andjointo manipulate text files. Many people usecutbut forget aboutjoin. -

Know about

wcto count newlines (-l), characters (-m), words (-w) and bytes (-c). -

Know about

teeto copy from stdin to a file and also to stdout, as inls -al | tee file.txt. -

Know that locale affects a lot of command line tools in subtle ways, including sorting order (collation) and performance. Most Linux installations will set

LANGor other locale variables to a local setting like US English. But be aware sorting will change if you change locale. And know i18n routines can make sort or other commands run many times slower. In some situations (such as the set operations or uniqueness operations below) you can safely ignore slow i18n routines entirely and use traditional byte-based sort order, usingexport LC_ALL=C. -

Know basic

awkandsedfor simple data munging. For example, summing all numbers in the third column of a text file:awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }'. This is probably 3X faster and 3X shorter than equivalent Python. -

To replace all occurrences of a string in place, in one or more files:

perl -pi.bak -e 's/old-string/new-string/g' my-files-*.txt

- To rename many files at once according to a pattern, use

rename. For complex renames,reprenmay help.

# Recover backup files foo.bak -> foo:

rename 's/\.bak$//' *.bak

# Full rename of filenames, directories, and contents foo -> bar:

repren --full --preserve-case --from foo --to bar .

-

Use

shufto shuffle or select random lines from a file. -

Know

sort's options. Know how keys work (-tand-k). In particular, watch out that you need to write-k1,1to sort by only the first field;-k1means sort according to the whole line. -

Stable sort (

sort -s) can be useful. For example, to sort first by field 2, then secondarily by field 1, you can usesort -k1,1 | sort -s -k2,2 -

If you ever need to write a tab literal in a command line in Bash (e.g. for the -t argument to sort), press ctrl-v [Tab] or write

$'\t'(the latter is better as you can copy/paste it). -

The standard tools for patching source code are

diffandpatch. See alsodiffstatfor summary statistics of a diff. Notediff -rworks for entire directories. Usediff -r tree1 tree2 | diffstatfor a summary of changes. -

For binary files, use

hdfor simple hex dumps andbvifor binary editing. -

Also for binary files,

strings(plusgrep, etc.) lets you find bits of text. -

For binary diffs (delta compression), use

xdelta3. -

To convert text encodings, try

iconv. Oruconvfor more advanced use; it supports some advanced Unicode things. For example, this command lowercases and removes all accents (by expanding and dropping them):

uconv -f utf-8 -t utf-8 -x '::Any-Lower; ::Any-NFD; [:Nonspacing Mark:] >; ::Any-NFC; ' < input.txt > output.txt

-

To split files into pieces, see

split(to split by size) andcsplit(to split by a pattern). -

Use

zless,zmore,zcat, andzgrepto operate on compressed files.

System debugging

-

For web debugging,

curlandcurl -Iare handy, or theirwgetequivalents, or the more modernhttpie. -

To know disk/cpu/network status, use

iostat,netstat,top(or the betterhtop), and (especially)dstat. Good for getting a quick idea of what's happening on a system. -

For a more in-depth system overview, use

glances. It presents you with several system level statistics in one terminal window. Very helpful for quickly checking on various subsystems. -

To know memory status, run and understand the output of

freeandvmstat. In particular, be aware the "cached" value is memory held by the Linux kernel as file cache, so effectively counts toward the "free" value. -

Java system debugging is a different kettle of fish, but a simple trick on Oracle's and some other JVMs is that you can run

kill -3 <pid>and a full stack trace and heap summary (including generational garbage collection details, which can be highly informative) will be dumped to stderr/logs. -

Use

mtras a better traceroute, to identify network issues. -

For looking at why a disk is full,

ncdusaves time over the usual commands likedu -sh *. -

To find which socket or process is using bandwidth, try

iftopornethogs. -

The

abtool (comes with Apache) is helpful for quick-and-dirty checking of web server performance. For more complex load testing, trysiege. -

For more serious network debugging,

wireshark,tshark, orngrep. -

Know about

straceandltrace. These can be helpful if a program is failing, hanging, or crashing, and you don't know why, or if you want to get a general idea of performance. Note the profiling option (-c), and the ability to attach to a running process (-p). -

Know about

lddto check shared libraries etc. -

Know how to connect to a running process with

gdband get its stack traces. -

Use

/proc. It's amazingly helpful sometimes when debugging live problems. Examples:/proc/cpuinfo,/proc/xxx/cwd,/proc/xxx/exe,/proc/xxx/fd/,/proc/xxx/smaps. -

When debugging why something went wrong in the past,

sarcan be very helpful. It shows historic statistics on CPU, memory, network, etc. -

For deeper systems and performance analyses, look at

stap(SystemTap),perf, andsysdig. -

Confirm what Linux distribution you're using (works on most distros):

lsb_release -a -

Use

dmesgwhenever something's acting really funny (it could be hardware or driver issues).

One-liners

A few examples of piecing together commands:

- It is remarkably helpful sometimes that you can do set intersection, union, and difference of text files via

sort/uniq. Supposeaandbare text files that are already uniqued. This is fast, and works on files of arbitrary size, up to many gigabytes. (Sort is not limited by memory, though you may need to use the-Toption if/tmpis on a small root partition.) See also the note aboutLC_ALLabove andsort's-uoption (left out for clarity below).

cat a b | sort | uniq > c # c is a union b

cat a b | sort | uniq -d > c # c is a intersect b

cat a b b | sort | uniq -u > c # c is set difference a - b

-

Use

grep . *to visually examine all contents of all files in a directory, e.g. for directories filled with config settings, like/sys,/proc,/etc. -

Summing all numbers in the third column of a text file (this is probably 3X faster and 3X less code than equivalent Python):

awk '{ x += $3 } END { print x }' myfile

- If want to see sizes/dates on a tree of files, this is like a recursive

ls -lbut is easier to read thanls -lR:

find . -type f -ls

- Use

xargsorparallelwhenever you can. Note you can control how many items execute per line (-L) as well as parallelism (-P). If you're not sure if it'll do the right thing, use xargs echo first. Also,-I{}is handy. Examples:

find . -name '*.py' | xargs grep some_function

cat hosts | xargs -I{} ssh root@{} hostname

- Say you have a text file, like a web server log, and a certain value that appears on some lines, such as an

acct_idparameter that is present in the URL. If you want a tally of how many requests for eachacct_id:

cat access.log | egrep -o 'acct_id=[0-9]+' | cut -d= -f2 | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

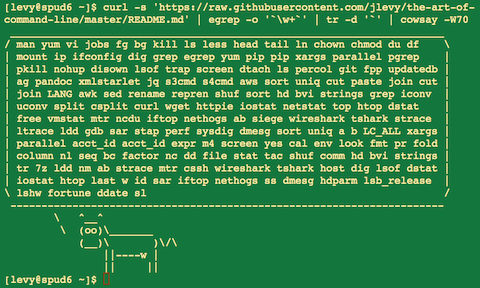

- Run this function to get a random tip from this document (parses Markdown and extracts an item):

function taocl() {

curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jlevy/the-art-of-command-line/master/README.md |

pandoc -f markdown -t html |

xmlstarlet fo --html --dropdtd |

xmlstarlet sel -t -v "(html/body/ul/li[count(p)>0])[$RANDOM mod last()+1]" |

xmlstarlet unesc | fmt -80

}

Obscure but useful

-

expr: perform arithmetic or boolean operations or evaluate regular expressions -

m4: simple macro processor -

yes: print a string a lot -

cal: nice calendar -

env: run a command (useful in scripts) -

printenv: print out environment variables (useful in debugging and scripts) -

look: find English words (or lines in a file) beginning with a string -

cutandpasteandjoin: data manipulation -

fmt: format text paragraphs -

pr: format text into pages/columns -

fold: wrap lines of text -

column: format text into columns or tables -

expandeunexpand: converte entre tabs e espaços. -

nl: adiciona números as linhas. -

seq: imprime números. -

bc: calculadora. -

factor: fatora inteiros. -

gpg: criptografa e assina arquivos. -

toe: tabela de entradas dos tipos de terminais. -

nc: ferramenta de debug de rede e transferência de dados. -

socat: socket relay e portas encaminhamento de portas tcp (similar aonetcat) -

slurm: visualização do tráfego da rede. -

dd: move os dados entre arquivos ou dispositivos. -

file: identifica o tipo do arquivo. -

tree: mostra os diretórios e subdiretórios como um árvore de dependências; comolsmas recursivo. -

stat: informações do arquivo. -

tac: imprime arquivos na ordem reversa. -

shuf: seleção random de linhas de um arquivo. -

comm: compara uma lista de arquivos ordenadas linha por linha. -

pv: monitora o progresso dos dados através de um pipe. -

hdebvi: dump ou edita arquivos binários. -

strings: extrai texto de arquivos binários. -

tr: tradução manipulação de caracteres. -

iconvouuconv: conversor de codificações de text. -

splitecsplit: divisão de arquivos. -

units: conversor de unidades e cálculos; converte furlongs por quinzena para twips per blink (veja também/usr/share/units/definitions.units) -

7z: Compressor de arquivos de alto desempenho. -

ldd: informações dinâmicas das bibliotecas. -

nm: símbolos de arquivos objetos. -

ab: benchmarking para web servers. -

strace: Debug para chamadas de sistema. -

mtr: melhor tracerout para debugar a rede. -

cssh: Visualização concorrente do shell. -

rsync: Sincroniza arquivos e pastas através do SSH. -

wiresharketshark: captura de pacotes e debug de rede. -

ngrep: grep para a camada de rede. -

hostedig: Consultas DNS. -

lsof: Arquivo de descritores dos processos e informações dos sockets. -

dstat: Estatísticas úteis do sistema. -

glances: Resumo em alto nível, de multi subsistemas. -

iostat: Estatísticas de uso do CPU e do disco. -

htop: Versão do top melhorada. -

last: histórico de logins. -

w: quem está logado. -

id: Informações sobre a identidade do user/group. -

sar: histórico dos estados do sistema. -

iftopounethogs: Utilização da rede por sockets ou processos. -

ss: Statísticas dos sockets. -

dmesg: Mensagens de erro do sistema e do boot. -

hdparm: Manipulação/performance de discos SATA/ATA. -

lsb_release: Informações sobre a distribuição do Linux. -

lsblk: Lista os blocos dos dispositivos: uma visualização é forma de árvore dos seus discos e partições do disco. -

lshwelspci: informações do hardware, incluindo RAID, gráficos, etc. -

fortune,ddate, esl: um, bem, isto depende de você considerar locomotivas a vapor e citações Zippy "úteis".

Mais conteúdo

- awesome-shell: Uma lista refinada de ferramentas do shell e outros recursos.

- Strict mode para escrever shell scripts melhores.

Aviso

Com a exceção de tarefas muito pequenas, o código é escrito de modo que outros possam ler. Junto com o poder vem a responsabilidade. O fato de você poder fazer algo no Bash não necessariamente significa que você deve! ;)

Licença

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.